Last Thursday marked ‘Time to Talk’ day. For some time beforehand I had told myself that it would be a good day to blog again to get people up to speed with my own health.

Then, because of my own health, I was not up to it on the day. Yep.

And, because of my own health, it has taken a disproportionate length of time to get this done at all. Ah, yep.

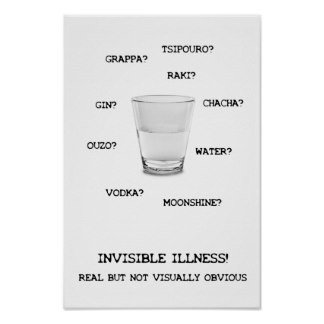

You may not be bothered about reading about mental health, or interested in why I behave the way I do these days. Please don’t feel any obligation to read on. I am not fishing for sympathy or even trying to make excuses. I would like to put down my thoughts on this blog, however; it is a difficult subject to bring up and worthy of some attention. Mental ill health is an invisible condition.

Since I got very ill in 2013, I have learned that I fail if I rush. I fail if I push myself too far. I fail if I get in a cycle of negative thoughts, eating habits or lack of discipline. I succeed only if I carefully pace life, keeping at things, finding the positives, respecting myself and living by faith, so it is still worth putting this blog post up even on the wrong day. Especially on the wrong day.

Every day can be a wrong day when you battle with the non-newtonian fluid that is time with a cloudy mind. I have no idea what day it is normally; it isn’t so important if you can’t juggle more than one thing well. To counter this I have lists and routines to ensure children are fed, dressed and delivered to and collected from school or clubs. Not knowing the day is like a mist that many of us experience when we’re busy. This state however is what my own mind is like most of the time. A dense fog. It’s out there, but I don’t know where to look – when I cannot see where I am going, I go to autopilot for many tasks. I cannot see where I have been either, as my memory is very patchy.

I make an effort to make myself remember things, but you may see me struggle to recall something from last week, last year or childhood, which may then suddenly come back into my head days later with real clarity.

That can be frustrating, unless I see it for what it is and allow myself longer to remember things; I only hope I’m not called up in court to tell ‘the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth’ when what is available to me is ‘the whole truth as I perceive it today, although there may be more I cannot yet access’. When I’m on a roll with an activity or in the zone mentally on a specific project I can sometimes stay focussed for far longer than usual, but as soon as I stop, that’s it. Gone. At other times I struggle to concentrate on a TV programme or a film or a book I’m reading. I don’t know why this is.

So when I do push myself too far, what does ‘failure’ mean? When my mind clouds or my memory or plans don’t make sense, that is. It is a sense of being lost, but it is also a lack of being able to function or be present in the moment. It is as if large parts of my mind are frozen. I can see tasks all around me but not only can I not arrange which order to do them in, but I cannot see how to do any given one. I have to reduce my focus intentionally and heavily against the flow of my wandering mind to one specific activity, and then hope and pray nothing comes along to throw me off. As I have a naturally divergent mind this can be quite draining mentally. If I am low emotionally it just costs too many spoons to achieve much in a day.

My daily spoon allowance is probably around 20 going by the chart here (which is not entirely accurate for me, but gives a general idea). My limits are nothing like as serious as dealing with the effects of ME, fybromyalgia or any of many other invisible illnesses, but it is real. If I give you my time, I will honestly think it is worthwhile doing so. If I don’t, it may well be down to self-preservation.

As an introvert, I love people, but I just don’t always love being around them. Being with people saps my mental resources very quickly. When I am very ill I cannot be around even my immediate family until I’ve recharged (currently this happens at least twice a day), and being in groups pays a very heavy toll; I need to make time to be alone on my own terms for several hours if I have had to be around a large group or in a space where I could not get away from people. This limits going into town, social events, sports, potential work situations and affects the rate at which I can do voluntary activities.

I get anxious internally, panicky and confused. Really confused. I may mess about or be facetious just to manage to remain in a place with others. Or I might hold one of my children close so that I don’t need to take responsibility for anything I can’t focus on. I forget things and my mind needs stimulus without saturation – so I find my foot tapping or my fingers moving about. I start to believe that I am not capable or that my slow pace of progress on tasks will mean I cannot achieve good things without a lot of support. The idea of making a phone call fills me with dread; even answering one can take a spoon or two from that day. I remind myself that I used to be a high-achiever and try not to blame myself for the slow going I find in my life today. I am writing a book. Even aside from the regular discipline needed for writing, I am having to be kind to myself when other things crowd in and use up the resources I have on any given day. Perhaps this will change in time, but until then I have to be content with baby steps and finding purpose and affirmation instead in the trivial and mundane activities I do at home or the exciting and useful things I do at church or out and about.

When I burned out nearly four years ago I was able to access counselling which was wonderful for talking over areas of my life that had caused hurt and working through some irrational thinking patterns. This has helped enormously. However, despite the counselling, and despite loving friends and family, an understanding doctor and appropriate medication (I tried to live without it for a year and am now back on it), I have realised that my mental health may be something which colours a huge amount of what I do. Where I was once highly attentive, I am frequently now oblivious. Where I was able to focus, I find I get overly tense and exhausted easily. I open many tabs in my mind (and on my computer) so that I can feel some sense of accomplishment, but do not finish all the tasks and forget what I am trying to do when I have to go off and collect the children or cook or see to the pets. As a result I start lots of ideas and struggle to maintain them.

I survive on cups of tea, on kind words, on prayer, on the promise of a book to come, on incremental improvements, on medication and on each of life’s many joys.

In the fog, joyful events and sad moments can each come as surprises. But I can also lose the sad moments more quickly as they get forgotten, and enjoy what is good by focusing hard on them and planning good things which will come around and surprise me.

The experience is like walking by trust with little sight, unaware of quite how the next chapter is going to unfold. It is not an experience I would have chosen, or would want to remain in any longer than I need to, but it is familiar now and I can work with it.

(photo by Ian Furst)

So God does the unimaginable – again. He separates. From day one he had been separating light and darkness. Now he separates from those who turned to follow him. A significant separation of a physical body with limits, before a spiritual meeting with his followers. The practicalities are not even that important. An ascent – lots of witnesses – and a junction in the story.

So God does the unimaginable – again. He separates. From day one he had been separating light and darkness. Now he separates from those who turned to follow him. A significant separation of a physical body with limits, before a spiritual meeting with his followers. The practicalities are not even that important. An ascent – lots of witnesses – and a junction in the story.

You must be logged in to post a comment.